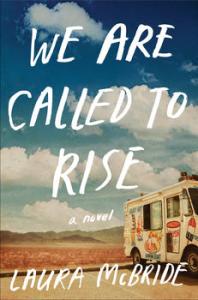

We Are Called to Rise

By Laura McBride

Simon & Schuster, June 3, 2014

320 pages, $25.00

Laura McBride’s debut novel captures the times in which we live with a story that skillfully weaves four narrative strands into a compelling and unforgettable tapestry. Set in the neighborhoods of Las Vegas, We Are Called to Rise tells the stories of a middle-aged woman whose marriage has suddenly collapsed, an eight-year-old Albanian immigrant boy whose family is struggling culturally and economically, and a recently returned Iraq War vet with a head injury and PTSD. The fourth narrator, who appears occasionally, is a social worker who becomes a Court-Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) for the boy.

The first half of the book introduces us to the lives of the main characters in alternating chapters. Avis is forced to cope with her hotel executive husband’s surprising request for a divorce when she should be overjoyed with the return of her son Nate from Iraq. He has completed police academy training and is about to join the Las Vegas Police Department. Nate’s young wife, Lauren, is even more thrilled to have him home. But something about Nate seems off. He’s impatient, prone to angry outbursts, and abusive to Lauren. So while Avis tries to determine where her marriage went wrong and what she should do next, she tries to save Nate and his marriage.

Bashkim is a sweet-natured, bright boy who is thriving in school and keeping a watchful eye on his little sister, Tirana. His parents own an ice-cream truck, a seemingly failsafe source of income in the Nevada desert; yet the Ahmeti family is in financial trouble. But his father was a political prisoner in Albania and remains hostile and even paranoid. He has isolated the family from everyone, including the local Albanian immigrants. Bashkim’s mother attempts to hold the family together and serve as a buffer between her husband and the children but bears the brunt of her husband’s discontent.

Army Specialist Luis Rodriguez is being treated at Walter Reed Hospital for a head injury and PTSD after two traumatic incidents in Iraq, which have left him wracked with guilt. He hopes to return home to Las Vegas to live with his abuela (grandmother), who raised him, until he can figure out what his options are.

The lives of these characters intersect in a moment of violence that is shocking and yet seemingly inevitable. The second half of the book explores the aftermath of an event that has left Bashkim’s future in limbo. The conclusion, while perhaps stretching the boundaries of plausibility somewhat, is emotionally fulfilling.

McBride’s ability to fully inhabit each of these characters is an act of supreme authorial empathy. The four narrative voices are distinct, idiosyncratic and, most importantly, instantly credible. You will love some of these people and respect others, but you will care about all of them. They are as real as your friends and neighbors.

Another strength of We Are Called to Rise is the pacing. Although alternating narrators can sap the momentum from a novel when not done well, McBride keeps the chapters to a manageable length and never keeps a character offstage for long. As a result, the story moves at a steady, increasingly tense pace.

There is a paradoxical sense of foreboding and hope in these pages; one feels the plot strands coming together inexorably, but McBride’s tone and the reader’s inherent optimism combine to maintain a feeling of hopefulness. These characters have such big hearts and good intentions that one roots for them despite knowing that circumstances rarely turn out as one would like; life so often chews up and spits out people that it can seem as if that is its purpose. But when we doubt the presence of God or an overarching purpose, we can find it if we look for the people who are trying to help. Readers will find those helpers in We Are Called to Rise.

My only quibble with the book is the overuse of names in dialogue. People simply do not use each other’s names this often when they’re talking. It occasionally detracted from the otherwise believable and mostly natural-sounding dialogue.

McBride has used the setting of suburban Las Vegas effectively. A longtime resident, she shows us the real Las Vegas, where working people live, love, go to school, marry, and raise children. Its neighborhoods are both Middle America and sui generis.

“Most Las Vegas children don’t grow up quickly. They aren’t fast like their coastal counterparts. In Vegas, children pass through their novel environment unconsciously, lacing up their cleats or humming to the radio while a parent maneuvers through the traffic on the Strip; while bare-chested men thrust pornographic magazines at open car windows, while women wearing a few feathers leer seductively from billboards, while millions of neon bulbs flash “Loosest Slots in Town” and “Babes Galore.” And still the children don’t notice. They’ve been taught not to notice, and it’s only the transplanted ones – the children who arrive from Boston when they are nine – who think to tell their friends back home about the naked billboards, the “Live Nude” signs, the doggy-sex flyers.”

“The families just off the Strip – the ones occupying mile after mile of nearly identical stucco houses – live conservative lives at home. Dad might be a dealer, mixing with high rollers at Caesar’s five nights a week, Mom might be a waitress, wearing a butt-skimming skirt at forty-seven, but home is for another life….It can be cloying, it can be surprising, but after a while, it simply becomes the way it is. And the good in it, the old-fashioned neighborly niceness of it all, is one of the reasons people stay in Vegas, stay even if they can’t explain quite why, even if they tell their friends they hate it, that the place is a dump, that off the Strip there is nothing to do, even if they worry about schools and bemoan the lack of art and feel stranded in the stark vastness of the Mojave Desert.”

As a lifelong Californian with two family members who’ve lived in Las Vegas for 15-20 years, I can vouch for the fact that this is as accurate a description of the real place as you will ever read.

Roberta, who provides the closest thing to an objective viewpoint, describes how these children go off to war, having been raised in a city with a large military presence.

“In Las Vegas, armed forces recruiting centers dot the landscape like Starbucks shops, across from every high school, near every major intersection. Everyone knows someone in the military. Thousands of people live on the base at Nellis; many thousands owe their livelihoods to it. Schoolchildren thrill to the roar of Thunderbird air shows, commuters estimate their chances of making it to work on time when they see four jets return to base in formation each morning.

“We send our children off, knowing that they will grow up, thinking the military will give them security, hoping they won’t be hurt, praying they won’t die, believing that ours is a patriotic choice. And our children come back with that war deep within them: a war fought with powerful weapons and homemade ones, a war fought by trained fighters and twelve-year-old boys, a war fought to preserve democracy, to extract revenge, to safeguard oil, to establish dominance, to change the world, to keep the world exactly the same. Yes, Vegas children fight America’s wars. These most American, least American of children, these children of the nation’s brightest hidden city: the city that is an embarrassing tic, a secret shame, a giddy relief, a knowing wink.”

McBride can write up a storm and, like the gods of old, she can throw down one perfectly aimed lightning bolt after another. At one point, Nate attempts to describe to Avis what it was like serving in Iraq. His explanation is the most comprehensive fictional depiction I have yet encountered of what it is like to fight in that complicated conflict and how it feels to come home to a completely clueless civilian population with the war still going on in your head.

“You can’t imagine, Mom. What it was like there. What we had to do. I thought I would die every day. Every hour…. You’re afraid of the kids. You’re afraid of the old ladies. You’re scared as hell of any rock you can’t see around, any building with a hole up high, where a gun might come through. You’re looking for it all the time. You’re seeing it even when it isn’t there…. And then you get back. And you’re home…It’s like a dream. Only you’re still so damn jittery. And I’m still looking for that hole in the wall up high, and the rock, and the kid with the bomb. I’m looking for it all the time. I can’t stop. If I hadn’t been looking when I was there, I’d be dead. I wouldn’t be here, Mom.”

Ultimately, though, McBride presents us with a vision of a world in which good people step forward and try to make someone’s life better, in which a “new normal” can come out of a tragedy. In which little things matter immensely.

“It all matters. That someone turns out the lamp, picks up the windblown wrapper, says hello to the invalid, pays at the unattended lot, listens to the repeated tale, folds the abandoned laundry, plays the game fairly, tells the story honestly, acknowledges help, gives credit, says good night, resists temptation, wipes the counter, waits at the yellow, makes the bed, tips the maid, remembers the illness, congratulates the victor, accepts the consequences, takes a stand, steps up, offers a hand, goes first, goes last, chooses the small portion, teaches the child, tends to the dying, comforts the grieving, removes the splinter, wipes the tear, directs the lost, touches the lonely, is the whole thing. What is most beautiful is least acknowledged. What is worth dying for is barely noticed.”

We Are Called to Rise will carry you away for a few hours, break your heart, and then put it back together tentatively, the fragile pieces held together by hope and love and the little things that matter.