In observance of Veterans Day, I thought it would be appropriate to share some books I’ve reviewed over the years that center the experiences of women at war and on the home front. Most of these books also explore characters’ difficulties in adjusting to life after war. While they are set during and after the Iraq War, the protagonists’ experiences are universal. These books are difficult but essential reading.

Sand Queen was the first novel about the Iraq War written by a woman. Helen Benedict, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, published a nonfiction book, The Lonely Soldier: The Private War of Women Serving in Iraq (Beacon Press), in 2009. It inspired an award-winning documentary, The Invisible War, and led to Benedict twice testifying before Congress on the issue of women in the military.

Sand Queen tells the stories of 19-year-old American soldier Kate Brady and Iraqi medical student Naema Jassim in alternating chapters. They encounter each other in 2003 when Brady is a guard at Camp Bucca, a makeshift prison in the desert near the Kuwait border. Kate is a naïve small town girl from upstate New York who joins the Army Reserve before 9/11, never expecting a war in the Middle East or to be called up and sent to a place like the Iraqi desert. Not surprisingly, she has trouble adapting to the harsh conditions at Camp Bucca. Her squad leader chooses Kate to serve as an occasional liaison to the local Iraqi civilians, but she is dubious.

Naema and her family have fled the chaos of Baghdad to stay with her grandmother. She joins a group of local residents who make a daily pilgrimage to the camp checkpoint to inquire about their missing male family members. Because Naema speaks English, she becomes the de facto spokeswoman for the group and interacts with Kate.

In following Kate and Naema, Benedict shows readers the contrasting experiences of two young women with good intentions in a war where little makes sense. Kate struggles to survive the boredom of long days in a guard tower keeping watch over endless stretches of sand that reach to the horizon. She attempts to bond with the other two women in her platoon, Yvette and “Third Eye,” but meets with only limited success. The women are guarded and defensive, aware of their tenuous position among the ranks of the men. The male soldiers are portrayed as ignorant, belligerent, and sexist louts, with only a few exceptions.

The conflicts sharpen when a sergeant assaults Kate and attempts to rape her. This is the turning point in her steady devolution from pleasant young woman to amoral robot soldier. She experiences the same emotional chaos as any victim of such an attack, compounded by the complexities of the military environment. At the same time, Naema is trying to learn the status of her father, who had previously been imprisoned and tortured by Saddam Hussein’s secret police. In exchange for Naema’s help communicating with the locals, Kate agrees to try to find out about Naema’s father.

As Sand Queen progresses, we observe the changes that the war has wrought on both Kate and Naema. For Kate in particular, it is a downward spiral of anger, hurt, paranoia, and contempt for the military’s fecklessness: she comes to despise the leaders who have supplied the soldiers with Vietnam-era equipment and seem generally unaware of what is needed to fight this particular war in this place, and she both fears and hates the enlisted men, who engage in a relentless pattern of harassment against the women, of both the sexual and fraternity hazing types. Her physical and mental health deteriorate steadily, but there seems little she can do about it.

Sand Queen is an important novel. The brutal power of the story, its fearless illumination of the realities of the Iraq War, and the quality of the writing make for a riveting read.

In her next novel, Wolf Season, Helen Benedict took a wider view, following the lives of three very different women in a small town in upstate New York.

Naema, whom we first met as an Iraqi medical student in Sand Queen, is now a widowed refugee doctor working in a VA clinic. Rin is an Iraq War veteran living on an isolated compound in the woods with her blind daughter. And Beth is struggling to hold down the home front with her troubled son while her husband is deployed in Afghanistan. The lives of these very different women slowly become intertwined in both expected and unexpected ways.

Benedict writes with a fierce intelligence suited to the subject matter, and with a deep compassion for these three good women fighting battles at home. She has done readers a great service by helping us to see aspects of this 18-year-long war that we might otherwise overlook and by asking important and uncomfortable questions about the true costs of war.

Cara Hoffman’s Be Safe, I Love You tells the story of returning soldier Lauren Clay and the challenges she faces in re-entering the lives of her family, friends, and civilian society. Hoffman’s book is both a fever dream of one soldier’s struggle with PTSD and a domestic drama about a splintered family and an isolated upstate New York town with little to offer the soldier or its civilian residents.

When Lauren Clay arrives in Watertown, her severely depressed father Jack and precocious younger brother Danny are understandably overjoyed to have her home and in one piece. Seemingly. But it soon becomes evident to Lauren’s boyfriend Shane, best friend Holly, and even to Danny that “she is not herself.” She tries valiantly to “act as if” she is well and happy to be home, and in occasional moments, she is. But there are warning signs: she is sullen, distracted, and preoccupied. She has a hair-trigger temper and is particularly annoyed when people fail to do what she says. As a sergeant with a platoon under her command in Iraq at age 21, she is used to giving orders and being obeyed without hesitation.

She refuses to talk about her experiences in Iraq or even what the war was like generally. It is a nightmare best ignored. When her father’s best friend, PJ, a Vietnam veteran, says she can tell him about Iraq later, she thinks, “She would not be wasting one more second talking about acts that shouldn’t be described and couldn’t be undone.”

Lauren is trying to escape from herself, with little success. “[S]omehow she’d forgotten that she had not returned at all. The woman she was supposed to be, was meant to be, would have been, could never exist at all now, and she was stuck dragging around this ruined version of herself. She owed it to the memory of her real self to get rid of this doppelganger that she was trapped inside….”

Although the plot was compelling, I was equally impressed by the quality of Hoffman’s writing, which alternated between a powerful directness and moments of haunting prose poetry. The supporting characters of Shane and Holly, Shane’s three uncles (so similar they are known as “the three Patricks”), Lauren’s eccentric Gulf War-damaged vocal teacher Troy, and her mentally ill father are well-drawn and credible, and they play a key role in making Lauren’s story realistic and riveting. The reader cares about these people and wants things to turn out well for them.

Alex Poppe’s Jinwar and Other Stories is an unsparing look into the world of war in the Middle East, focusing on Syria and Kurdistan (Northern Iraq). The title novella and five accompanying stories take readers behind the scenes of the news reporting that has created the images we have about the people, places, and politics that have dominated foreign affairs for two decades.

These are gritty, closely observed depictions of women in the midst of the chaotic world of war and post-war situations, with countries working at cross-purposes both military and diplomatic, and NGOs attempting to alleviate the suffering and facing obstacles from every direction. In short, it is hellish.

“Jinwar” is a four-part story that follows the protagonist during her stint as a nurse’s aide stealing Xanax in a VA hospital before moving first to a riverside hot dog truck somewhere in America during Wiener Week and then to a group of women from an NGO navigating complicated and often dangerous relationships with each other and the men of Northern Iraq. It finishes when she arrives at Jinwar, “a women-only, ecological self-sustaining village … built from scratch by Syrian Kurdish women … a place for women who wanted to live independently and break free from violence.” If you read only one story about the Iraq War, it should be “Jinwar,” which presents a multifaceted view of the impacts it has on the various participants.

In “V,” a lonely Kurdish-American teenager in Oakland becomes enamored with a young female rebel leader in Kurdistan before being confronted with the reality of shifting alliances and conflicting loyalties in Kurdistan.

“Kurdistan” introduces another teenage girl, this time from Nashville, who is moving to Kurdistan to live with her aunt after her mother dies (her father died eight years earlier while working as an interpreter for the U.S. Army in Iraq).

Poppe balances the struggles of her characters with lots of gallows humor to leaven the brutality and senseless actions of a long list of military, rebel, and jihadist groups (primarily ISIS), all of which are oppressively patriarchal.

Siobhan Fallon’s 2011 collection, You Know When the Men Are Gone, is one of the few books that focuses on those left behind to wait at home: the wives, children, family members, and friends. Fallon, who is married to an Army officer, lived on the army base at Fort Hood, Texas while her husband served two tours of duty in Iraq. She became fascinated with the lives of the women on the base and the culture of coping created by those in the “rear detachment.” The eight interconnected stories here offer readers some insight into the many challenges faced by civilians who have married into the military life. This is a world that receives little attention and about which we civilians know next to nothing. It is the invisible home front of the “war on terror.”

Fallon focuses her attention on wives who are adjusting to life as a single parent; they are trying to get on with their lives despite their loneliness and anxiety about their spouses in the Middle East, the burdens of child-rearing, worries about family finances (always tight), and frequent moves to new bases in strange places. Her personal experiences inform these powerful stories with a realism that makes them feel almost like non-fiction. We meet a strange and struggling war bride from Serbia (the opening title story), a mother struggling with both cancer and a sullen and rebellious teenage daughter (“Remission”), a young wife who fears her husband is having an affair with a female soldier while in Iraq (“Inside the Break”), another wife who wants out of the military life despite the recent return of her seriously wounded husband (“The Last Stand”), and a spouse trying to make sense of her husband’s horrific death in a fire-bombed Humvee (“Gold Star”). Through their circumstances and reactions, we begin to get some idea of what the hidden side of war is like.

The reader comes away from this book understanding a side of the war he or she was unaware of before. You Know When the Men Are Gone is an indispensable contribution to the literature of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and military life in general.

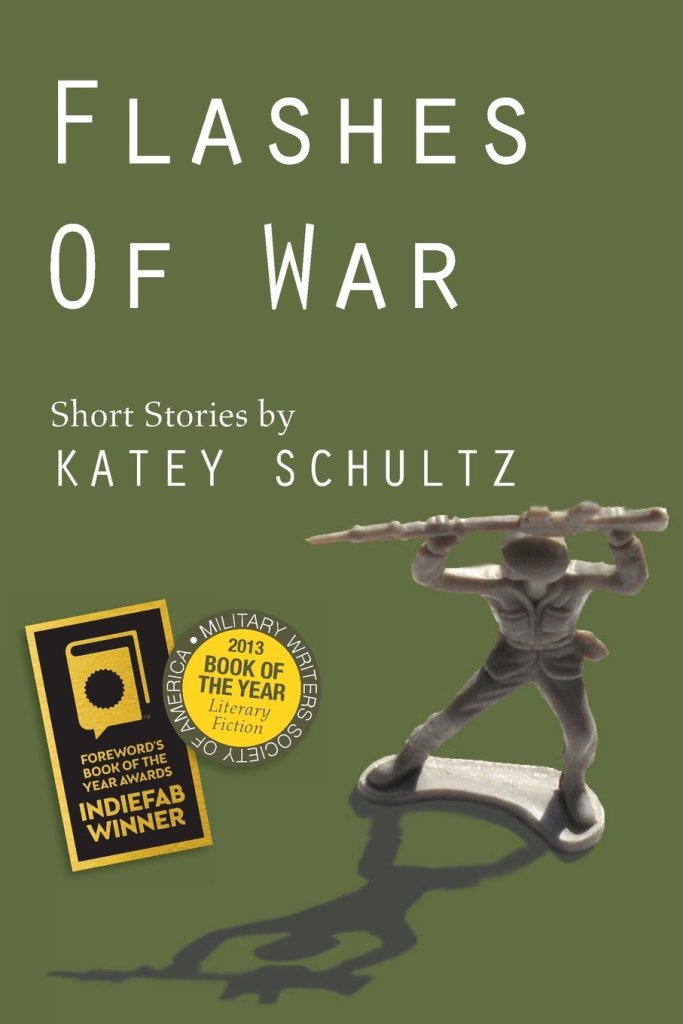

Katey Schultz’s stellar collection of flash fiction, Flashes of War, features 31 selections, most of which range in length from two to five pages, although there are a handful of stories in the 12 to 17-page range that anchor the collection.

While each story has its own compact power, in part precisely because of its conciseness, the cumulative effect of reading these 31 stories over 164 pages is like watching one of those gut-wrenching videos of dozens of people affected by the war. We hear from soldiers on duty, bored and feeling useless at the FOB (forward operating base), training to become warriors, or returning home profoundly changed. We hear the heartbreaking voices of the women left behind, waiting and chewing on their fingernails: wives, girlfriends, mothers, sisters. And we also, crucially, hear the voices of Iraqis and Afghans — civilian, military, insurgent, Islamist, young and old, male and female. All are trying to make sense of surreal circumstances that defy interpretation by the rational mind.

Flashes of War opens with the page-long tone-setter, “While the Rest of America’s at the Mall,” which points out the contrast between the men and women at war and the other 300 million Americans. “With the Burqa” is the first-person narrative of a young woman in Kabul, Afghanistan whose father was recently killed. “With the burqa, it was like this: the world came at me in apparitions, every figure textured by the mesh filter in front of my eyes. In a city with so much death, it was easy to believe half the people I saw were ghosts. Women sat like forgotten boulders along the sidewalks in Kabul. We begged. We prayed.”

One of the longer stories, “Home on Leave,” details the experiences of a young soldier on leave in Arkansas. He is perplexed by the various reactions to his return from Iraq. His family and friends treat him like a hero, but he is uncomfortable with the attention, more than he received even as a star wrestler in high school. His dirty little secret is that he has not seen combat. “Amputee” follows a wounded soldier at Walter Reed Medical Center, 112 days into her treatment and recovery.

Schultz breaks the reader’s heart in a hundred different ways in these stories. But she leaves your mind and your conscience intact, pondering the hidden costs of war.