Lily King grew up in Massachusetts and received her B.A. in English Literature from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her M.A. in Creative Writing from Syracuse University. She has taught English and Creative Writing at several universities and high schools in this country and abroad.

King’s first novel, The Pleasing Hour (1999) won the Barnes and Noble Discover Award and was a New York Times Notable Book and an alternate for the PEN/Hemingway Award. Her second novel, The English Teacher, was a Publishers Weekly Top Ten Book of the Year, a Chicago Tribune Best Book of the Year, and the winner of the Maine Fiction Award. Her third novel, Father of the Rain (2010), was a New York Times Editors Choice, a Publishers Weekly Best Novel of the Year, and winner of both the New England Book Award for Fiction and the Maine Fiction Award. It was translated into several languages.

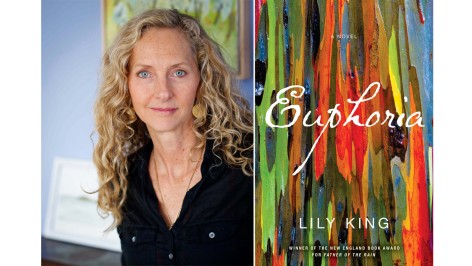

King’s latest novel, Euphoria, was released in June 2014. [Read my review here.] It has won the inaugural Kirkus Prize for Fiction and the New England Book Award for Fiction 2014. Reviewed on the cover of The New York Times Book Review, Emily Eakin called Euphoria, “a taut, witty, fiercely intelligent tale of competing egos and desires in a landscape of exotic menace.” The novel has been translated into numerous languages, and a feature film is underway.

King is the recipient of a MacDowell Fellowship and a Whiting Writer’s Award. Her short fiction has appeared in literary magazines including Ploughshares and Glimmer Train, as well as in several anthologies. (http://www.lilykingbooks.com/about/)

I write by hand with a pencil in a spiral notebook. That’s how I’ve been writing ever since grade school, and it’s how I’m writing these words right now, though when it gets to you, all traces of that initial draft will be gone.

I like the feel of lead scraping onto paper; I like the way the pencil tip starts to slope in one direction, creating a thick side and a thin side, and how with those two surfaces you get a subtle calligraphic effect. I like the way my brain works when I have a pencil in my hand. Just holding it seems to make the thoughts come, like the way putting food in front of your mouth makes the saliva run, or just smelling coffee makes you feel more awake. On paper you can write in the margin or squeeze ideas in between lines; you can use arrows and balloons and carets to rearrange and to add; you can draw pictures of what you’re trying to describe and you can read what you’ve crossed out and realize the way you said it that first time was better than all the other attempts, and you can run on and on because writing by hand does that, makes your sentences long and serpentine, like a river whose ending you don’t see until you turn the last bend.

When I was in high school I took a creative writing class for two semesters, junior and senior spring. We had to hand in a short story, three and a half pages of “polished prose,” my teacher said, every Monday morning for five months. I would often wake up Sunday mornings with a story already running in my head, the voice of it clear and sure (the editor, that savage critic, wakes up more slowly), and I’d grab my notebook and pencil and start writing it down. I don’t have a lot of memories from high school that are warm or pleasurable to me now, but thinking back to those Sunday mornings writing a story due the next day is one of them.

Photo by Winky Lewis

Photo by Winky Lewis

I still write like that, at first, when the story is new and I wake up with it and reach for a notebook. It connects me to my younger self, that sixteen-year-old girl with a broken family, big fears, and terrible hair, writing, it would seem (if you could see her from a high corner of her room—a new room, because her mother just remarried and she’s moved into her stepfather’s house) for her life. Writing about her old family and her new families, writing about her father’s anger and second divorce and breakdown (they won’t take that story for publication in the school’s literary magazine, “too personal”, she’ll be told, though “write what you know” is the mantra in her CW class), writing about unrequited love of all kinds, over and over.

I write the first draft of my novels in pencil in spiral notebooks exactly as I used to write those first short stories. I start at what I think is the beginning of the book and move mostly chronologically through to the end. Occasionally there is a back story, or a side story, but mostly I move forward through the notebooks. I section off the last 20 pages of each one for notes, for ideas I have for future chapters or for chapters I’ve already written. These ideas can be general (“Everything needs to feel relentlessly claustrophobic in this house”) or specific (“Have him give her his dead brother’s glasses”). They can be whole scenes, lines of dialogue, a fragment of detail. When the notes start to accumulate and confuse me, I make a timeline by drawing a line across the top of a page and little vertical notches along it and I make a list of all the things I think will happen, little and big moments I am trying to get to.

E.L. Doctorow once said, in a Paris Review interview, that he tells his students that writing is “like driving a car at night: you never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” The timeline is one moment followed by another, my few feet of illumination at a time. Some of those ideas, once I get to them, are ignored. Others I try out and quickly know they don’t work. I go down one road, then another. Often I have no idea where we’re going to end up. I know where I want the characters to be emotionally, but I don’t know yet what needs to happen to get them there. I thought my novel Father of the Rain was just going to have two parts, until I woke up in the middle of the night, the night President Obama had been elected, and realized there was a whole third section to the book. I’d handed in my most recent novel, Euphoria, to my agent when I was turning off a highway exit, late to meet a friend for lunch, and saw a whole new ending play out in my head. At the stoplight I scribbled it down on a pad I keep in my car.

At the back of my notebooks I keep a log, a punch clock of sorts. When the writing day is done, I write the date and how much I’ve written. A good day for me is 3-5 notebook pages, but there are days, many, many days when I don’t write that much. Some days I write one page, or a half page, or one line. I do not force myself to stay in the chair until I’ve written a certain amount. I cannot do that. I know there are writers who force themselves to stay in the chair until they’ve written a certain number of words each day, but those writers, I am certain, don’t have children who need to be picked up at school. I try not to beat myself up about the days of few words. A lot of work is being done that is not writing, a lot of thinking, note-taking, and listening. Because the imagination is always working, churning up something. It’s the writer’s job to listen carefully.

No one else can read my handwriting with much success. I can barely read it myself. It is small, mostly finely calibrated squiggles. Sometimes I have to trace these marks later with a pencil to figure out what I’ve written. But the transfer of my handwritten words to the computer is my favorite part of the process, and the most valuable. It is the closest I can get without weird anachronistic imitation to the days when writers had to retype each draft before handing it in to their editors. That step, rewriting every sentence, holding each word up to scrutiny, deciding what is good enough to go on the computer and what needs to stay in the notebook, is essential. And it’s joyful. Before this, when the page is blank, writing is scary and stressful. The unknowns too great. And afterward, there are too few unknowns, and things feel locked in place and small changes can unravel too much fabric. But in this stage it’s still fluid, not yet set, still receptive to reshaping. When I type in that rough draft I can hear it like I did not hear it as I was slowly, day by day, writing it, and like I will not hear it again as I read it over. I can hear it and play with it—it is both a fully creative process and a fully editorial one. It is the one time when the critic and the creator are both working full steam and in harmony. The rough draft relies solely on the creator, the critic banished from the room, while the future drafts demand more and more from the critic and less from the creator who shrieks at every change and chop. But in this step they are in balance. They are a team, passing the ball up the field easily and swiftly.

Sometimes I type up each chapter when it’s finished. Sometimes I go months without typing a thing. Once I spent sixteen weeks putting a whole notebook and a half onto the computer. Eventually everything gets transferred and printed out and read and edited, read and edited, many times. The notebooks have been forgotten by then, pushed off the desk, flung in some corner of my study like empty chrysalises, dry husks of words. The story has moved on, the scrape of pencil against paper forgotten. Until the next time, the next idea, the next Sunday morning when a new story starts spooling out and I have to try to catch it before it’s gone.

This is beautifully written and explained. Makes me want to put away my computer an pick up my pen.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Worth Getting in Bed For and commented:

Euphoria is one of my favorite reads and I enjoyed reading about Lily King ‘s writing process. I hope you do, too.

LikeLike

Euphoria is one of my favorite reads and I enjoyed reading about Lily King’s writing process so much I had to reblog!

LikeLike

This post really made me want to do two things: read Euphoria to discover the art of Lily King and take up my pen and just write. I hope I can achieve both 🙂

It is also very interesting and thrilling reading about an author’s creative process as it can be so different from one person to another. Thank you for posting this!

LikeLike

I recently decided that I need to have a writing date with myself. From 7:00 to 9:00 PM each Thursday, I leave my husband at home, go to a specific cafe and sit at the same table, and write by hand for two hours. I started doing this because I read Syllabus by Lynda Barry. In that book, she describes how there is a connection between creativity, the hand moving, and the brain. It’s not a fully explained theory, but in the book you can read some of the activities that her students do. It sounds fascinating, and these are very lucky students, indeed. But there is something that allows a writer to step back when she’s transferring the handwritten to the computer that makes her a better editor and clearer thinker. I think there’s an element of forgiveness, like, “Oh, I hand wrote that, so of course there’s no editing and it’s not the best, so I’m happy to change it!” Thanks so much for sharing, Ms. King!

LikeLike